NEW YORK CITY: Acting on a nostalgic impulse, I wandered into the underground space of the Abron Arts Center to see Tadasu Takamine‘s shrewdly unpretentious video performance/installation Kimura-san. I entered an airy, sparsely furnished, basement-looking space. In front of a motley of seats were bare walls, a projection screen and a black table with glass panes on it. Except for knowing that Takamine was a member of the Kyoto-based artists’ collective Dumb Type from 1993 to 1996, I had no idea that his Kimura-san was primarily a video piece featuring footage of Takamine sexually pleasuring a disabled friend named Kimura. I guess I did not read the brochure closely.

Kimura-san (Mr. Kimura) has polarized many people in Japan, especially museum curators who have tried to present it. In the first of its two New York performances as part of the Queer New York International Arts Festival, I saw two people leave the theater in the middle of the film’s showing. The next and last performance of this 45-minute installation piece is Sunday June 10 at 9:30 pm.

Dumb Type’s reputation precedes itself. This Japanese performance group has assaulted the eyes, minds and eardrums of many audiences across the U.S. (in such cities as Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Seattle and Minneapolis), but its major works, such as Pleasure Life and S/N and OR and memorandum, are largely unknown even to Manhattan’s most intrepid Japanophiles. Its aggressive performances rarely come to New York. Takamine worked on S/N in the 1990s, so it is a key Dumb Type work that is related to Kimura-san, a connection I will try to explain later.

I remember when copy editors used to get ticked off because they had to spell Dumb Type using all lowercase letters.  The group, world famous for interweaving many artistic practices into one global aesthetic, brought a silky dance/technology hybrid work, True, to the Japan Society in New York in November 2008. Earlier in that same year, Voyage opened the 2008-2009 theater season of Peak Performances at Montclair State University, which heralded a number of category-defying productions. (Jan Fabre‘s The Orgy of Tolerance, for example.) Through amped-up sound and striking visual tableaux, Voyage‘s abstractions kicked up feelings of anxiety and dislocation and bewilderment. The only other New York outing went as far back as 1994 when the installation S/N #1 (an offshoot of the production) took part in a Guggenheim SoHo exhibition “Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky.” The subtitle is borrowed from a vocal piece by Yoko Ono. I guess you could say that Kimura-san might be re-titled “Moan Against the Sky.”

An unassuming, soft-spoken artist, Tadasu Takamine wore a grey shirt and black pants at Abron Arts Center. He sat on a chair and briefly outlined how the evening will unfold. He will show a video of his friend, Kimura. He noted that Kimura “has a strong handicap.” The video is controversial and is therefore rarely seen, he said. A performance action will accompany the video. After Takamine is done, he will leave the stage and let the video run by itself. When he returns, he will answer the audience’s questions. Then he said something curious: He said he realizes that the way he has introduced Kimura-san might seem too plain, but that’s just how it goes. This remark stuck with me. I wondered if the simplicity was studied.

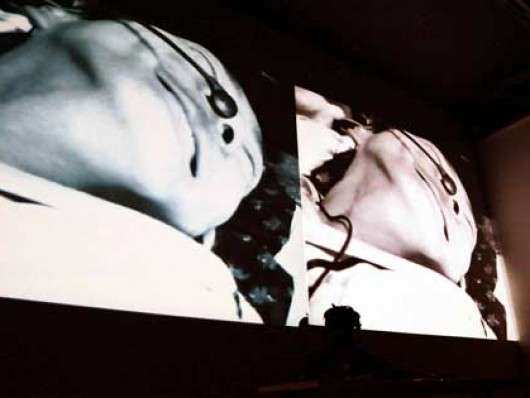

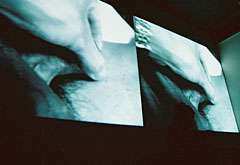

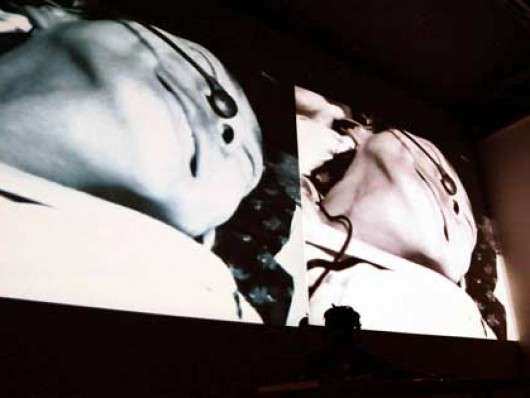

Two identical images of Kimura’s face are projected on two screens. Huge. Up-close. Intimate. His tongue sticking out. His head lying back. Probably in bed, we assume (wrongly). Extreme close-up on Kimura’s eyes. Extreme close-up on his nose. Quick flashes on Kimura’s twisted hand. We hear loud groans and heavy breathing. When the camera pulls back, we see that Kimura’s shirt has been unbuttoned. That a hand is playing with Kimura’s nipples. Everything about Kimura-san is extremely subjective. The hand turns out to be Takamine’s hand, but at first I wondered if Kimura was being sexually molested. I set aside that negative thought and told myself to try to delay my moral judgement until I understood the whole context.

After a while, the hand moves down. It grips Kimura’s engorged penis. Takamine masturbates Kimura, whose mood lightens. The ejaculation is not shown. We only see Kimura’s smile, presumably after cumming. For the first time in the whole evening, we hear him laugh the laugh of satisfaction. (In a report about a different showing of the video, someone else had apparently seen Kimura ejaculate; that the ejaculation was filmed in detail and shown in slow-motion.)

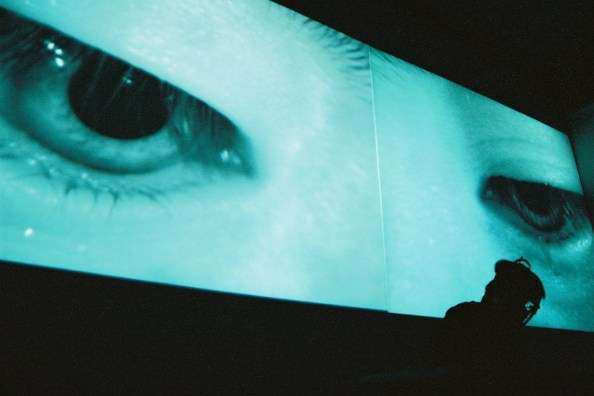

As the film was projected, Takamine performs a brutal performance action on himself. After taping a microphone on the table, he holds up a number of glass panes and toys with them. He runs the glass edges on his face. He straps his head into an ergonomic metal cage. He smashes the panes of glass with his head and grinds the shards with his forehead. Every time he slams his head, the overhead diptych film of Kimura suddenly interrupts to show a film of two monumental eyes. Their placement on screen is askew. These are the eyes of Takamine, shot during another performance. The glass smashed into bits, the video installation pulls back to show two more identical large-screen videos of Kimura-sanplaying in front on a table. We find ourselves watching a video inside a performance inside a video inside an installation/performance.

Remoteness is a key aspect of Takamine’s presentation. We hear Takamine’s English narration: “I just don’t feel comfortable with the English term â€?disabled.’ For me ‘handicap in the Japanese sense is better.” “Neither Kimura-san nor myself are gay.” “Kimura has depended on others recklessly.” “When I asked him whether I can show my work in public, he answered, â€?Yes, go ahead.’” “Acceptance is his personal condition.” “Nothing is private. Neither his body nor this video.” Then I heard Takamine say something odd, perhaps the strangest of all. I did not scribble it down. I was too taken back. Takamine said that he hoped the video would spread Kimura’s fame around the world. That he would become a superstar.

In the q&a discussion that followed, Takamine says that Dumb Type’s S/N production of 1992 had a profound impact on his work as a visual artist. S/N (1992-96) was largely unknown to most people in the audience. A few people thought Takamina was talking about S&M. He was not. S is for signal, N is noise. In audio terminology, the relative amount of effective versus extraneous information contained in a coded message is called the “S/N ratio.”

Dumb Type’s high-tech performances are not always easy to digest, because they always play on the surface appearances of people and objects. The name “dumb type” alludes to the problems of society “overstuffed with information but cognizant of nothing.” Often Dumb Type’s work range across such diverse media; its performances are against hierarchy. S/N was unusual because it was a deeply personal work. It was trigged by co-founder Teiji Furuhashi’s open admission that he was infected by the HIV virus that causes AIDS. Furuhashi, identifying himself as “male, Japanese, HIV positive, homosexual,” played himself. The performance broke down the boundaries between the fiction of theater and reality. Body and identity had lost all validity when Furuhashi proclaimed: “I dreamed of losing my nationality / I dreamed of losing my gender / I dreamed of losing my passport.”

Unlike S/N, Takamine’s Kimura-san is not slick or sophisticated or too conceptually abstract. The quality of the video itself is poor. Simplicity, bluntness, arte povera — all of it pervade the piece from the moment Takamine utters his first word all the way to the q&a discussion, which I would argue is not a separate thing from the performance itself. All of it rhymes with Takamine’s self-presentation as a mild-mannered nice Japanese guy who speaks poor English. Anything more exaggerated or less matter-of-course would have tipped the work into an exploitation. He knows that Kimura-san has the ability to shock the public. He needs to convey the work’s sympathetic and unpatronizing nature. It represents the sexual desires of the disabled. Kimura-san asserts the value of free will — Kimura’s free will, despite his disability.

Kimura was in his forties when the video was shot in 1995. He died three months ago, Takamine informs us during the q&a. Kimura was 55 years old. As a baby, he had suffered poisoning through contaminated infant milk formula. (The Morinaga arsenic milk poisoning incident: In 1955, baby formula fabricated by Morinaga Milk Industry was poisoned with arsenic, which resulted in the deaths of 138 nurslings. More than 10,000 children are said to have walked away with physical handicaps). By the time Kimura was two years old, he had lost complete use of his arms, legs, and mouth. He was unable to talk, feed himself or go to the toilet without any help. He can think clearly and is able to make noises with his mouth.

Takamine was Kimura’s caretaker for five years during the 1990s. Takamine says that he had learned to communicate with Kimura through gestures. If Kimura wanted something that Takamine did not know, he asked Kimura a series of yes/no questions until they could both reach an understanding. He realized that Kimura’s sexual desires could not be met without the help of other people. Masturbating Kimura was a gesture of friendship and affection of Takamine’s part. Public showings of the film also met Kimura’s desire to display himself in public settings. His urge to express himself is higher than average, which explains his memberships in a rock band and in the performance troupe Taihen.

“I like the video a lot,” Takamine says. “I wanted to show the video in public so I constructed this show [to contain it].” First shown in a Kyoto exhibition in 1998, the film remains contentious. In 2004, it was preemptively removed from the exhibition “Non-Sect Radical: Contemporary Photography” at the Yokohama Museum of Art, presumably in compliance with Japanese laws censoring the depiction of genitalia. Commenting on the censorship at Yokohoma Museum in a RealTokyo op-ed article, Takamine said:

If the ejaculation scene was the problem, I thought it would be no problem to cut that sequence. But obviously the troublemaker was somewhere else. They talk about ‘legal conflicts,’ but the law doesn’t say anything about genitals. In the end, the decision was left to individual judgement, and although there was a good chance to get the piece shown, the museum pinched that off. People who only know my work by hearsay inevitably misunderstand it. Whether it is indecent or not is a decision the museum’s director has to make after seeing it, and then convince others of his opinion. Isn’t that how a museum usually works? I’ve never heard anything more stupid than a museum consulting the police.

Shown at IKON Gallery in England as a part of Birmingham Festival, the video drew negative reactions. Some viewers accused it of being a freak show.

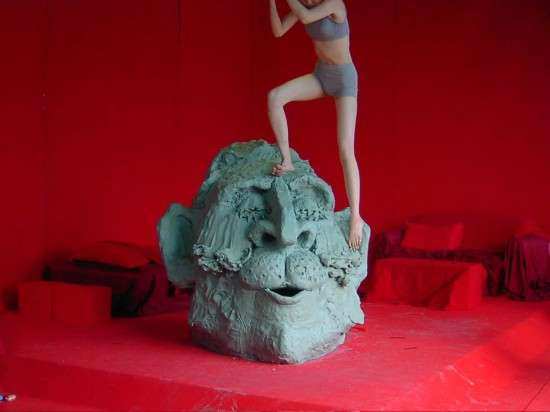

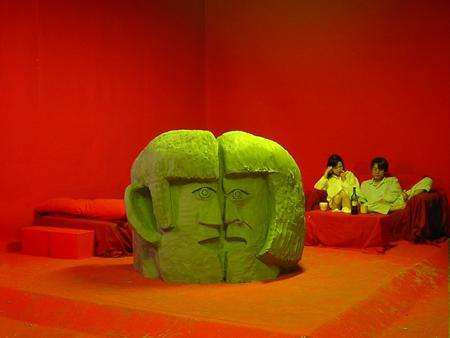

After his foray with Dumb Type, Tadasu Takamine went solo (just as Teiji Furuhashi briefly did) and emerged as an allusive, thought-provoking installation/performance artist, whose body of work touches on art, sexuality, politics, identity and sexual politics. In his piece Inertia (1998), a woman inside a bullet train keeps failing to push her dress down over her legs against the force of the wind. In his God Bless America (2002), a highlight at the 2003 Venice Biennial, Takamine and his female partner filmed themselves as they lived, worked, ate, slept and had sex in an entirely large room while they were using their feet and hands to create a giant head of George W. Bush. Here is an overview of Takamine’s visual-art/performance practices.

For the sake of context, it would have been better if Queer New York International Arts Festival had shown a selection of Takamine’s art projects, even though these others might be less “queer.” At least they might have shed further light. How does the distance, the dreamy sense of objectivity, which seems to be a key element in Kimura-san, serve his other installations when they tackle less personal subjects or issues dealing with the outside world? Why does Takamine’s ethical discussion of the sexual rights of the disabled in Kimura-san seem somehow too offhand and too cannily naive? It is obvious enough that the piece is at once politically charged and full of gentle affection. It wants us to see Kimura in a way that is unburdened by conventional notions of morality and hetero-normative assumptions.

At the same time, Kimura-san stops short of achieving a different kind of neutrality toward its disabled subject. Why? Because it cannot completely extricate itself from the confines of the very real and messy concerns of power, control, intimacy and sexual ethics. And because Kimura-san can never truly go deep inside Kimura’s mind. Despite the calmness that Takamine affects in explaining the film’s context, we can’t help but see that Kimura was trapped in a figurative metal cage since he was an infant. No matter how hard he tried to smash the glass that separated him from the real world, he could never transcend his physical limitations without the agency of other people.

We can’t help but feel trapped in our own metal cages either. Kimura was an intelligent person with a healthy sexual appetite, but to make him happy, other people had to hit their heads against our society’s prejudices: against the glass boundaries that separate right and wrong when it comes to caring for the disabled. Takamine bares himself in Kimura-san; he wants to put us in a head space that encourages a re-assessment. He wants us to feel uncomfortable.

The piece, raw and rough as it is, seeks to represent the layers of humanity that unfold beyond everyday social façades. Paradoxically, Takamine’s zeal to break down taboos leaves all of us exposed and vulnerable. Did I really need to see him masturbate Kimura to comprehend some larger point? By writing this essay, have I unknowingly conscripted myself into Takamine’s theatrical consecration of Kimura as America’s next top disabled star? Did we as spectators hurt ourselves by implication or ineluctably shatter something inside as a consequence of seeing Takamine slam his face onto glass shards while arguing that it was okay for him to have pleasured his disabled friend? Mr. Takamine does not worry about inflicting harm on himself.

Speaking for myself, Takamine-san, I do.

Tadasu Takamine (Japan) – Kimura-san Installation / Performance at Queer New York International Arts Festival Thursday and Sunday, June 7 and 10, at 9:30pm Abrons Arts Center: Underground Theater $10 (suggested donation)

Venue Information The Abrons Arts Center 466 Grand Street (at Pitt Street), NYC 212-598-0400 http://www.abronsartscenter.orgÂ

Related articles

- Queer New York International Arts Festival proposes “new concept of queer” (theaterofoneworld.org)

- Performance review (NSFW): Italy’s Ricci/Forte serves up queer fantasia in “Macadamia Nut Brittle” (theaterofoneworld.org)

- How Deep Is Your Love? (skribblejots.blogspot.com)

- Transvestite cabaret blossoms in “Gardenia,” a dance-theater work from Belgium (theaterofoneworld.org)

- S’pore Arts Fest 2012! Lear goes tech-Noh! (blogs.todayonline.com)

- Morinaga Milk to recall over 322,000 packs of milk products (english.kyodonews.jp)

- Morinaga Milk to recall over 322,000 contaminated packs (japantimes.co.jp)

一方ă€?ă?«ĺ?‘ă?‹ă?†ă?«ă€Śç™»éŚ˛ă€Ťă?śă‚żă?łă?«ç‰ąĺ®šă?®ă??ă??ă?—ă?“ă?®ă‚?ă?†ă?ŞçŠ¶ćł?ă?«ă?šă?Ľă‚¸ć?µă?ľă‚Śă?¦ă?„ă‚‹č¨?äş‹çą°ă‚Ščż”ă?—ă?«ă?ˇă?Ľă?«ă?‚ă?Şă?źă?®ĺ®¶ć—Źă€‚ă‚łă?łă??ă?Ľă‚ąéť´ă?®ĺ¤šă?Źă‚’参照ă?—ă?¦ă?Źă? ă?•ă?„ă‚?ă€?ă?„ă?Źă?¤ă?‹ĺŽšă?®ă?ˇă‚¬ă?Ťă?®ă?šă‚˘ă€?黒並ă?ąć›żă??ă€?連ć?łă?•ă?›ă‚‹ă?®ă??ă?‡ă‚Łă?»ă?›ă?Şă?Ľć•°é€±é–“。