By Randy Gener

LONDON and STOCKHOLM | Bob Dylan is a terrible crooner. So what if he won the Nobel Prize in Literature for the songs he wrote?

What was once the grit in the great man’s voice now sounds as extra-coarse as sandpaper rubbing concrete. Don’t take my word for it. David Bowie agrees; he famously compared Dylan’s voice to “sand and glue.”

And yet Dylan became the first musician to become a Nobel laureate. Why? Because his dense, enigmatic songwriting has always resonate as true poetry. Because this time the Swedish Academy has set off a debate about whether song lyrics have the same artistic value as poetry or novels.

This month, the 75-year-old singer-songwriter confounds expectations once again. He turns out to be a prolific visual artist — a painter and sculptor to be exact. (Bill Clinton owns one of his metal works.) A new exhibition of Dylan’s art, “The Beaten Path” — made up of sketches, paintings in acrylic and watercolors, ironworks — just opened at London’sHalcyon Gallery, where it runs from November 5 to December 11.

The exhibition could not have arrived at a more opportune moment. Worldwide interest in the veteran American troubadour has soared after his surprising choice as this year’s winner of the Nobel Prize, and the show is one of the most extensive displays ever mounted of his drawings, watercolors, acrylics and ironworks

A day before the London show closes, Bob Dylan is expected to hobnob and be curtsied in Stockholm where he will formally accept in person the Nobel Prize honor that now elevates him into the company of T. S. Eliot, Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison and Samuel Beckett. If he can fit it into his demanding tour schedule, the gallery hopes he will stop off in London to visit the show.

The elusive Dylan, however, may be a no-show in Stockholm, according to two recent reports. No explanation was given.

The critical appraisal of Bob Dylan now pivots to a new question. Is he a good — or great — artist? Is he America’s new Picasso or Magritte or Pollock?

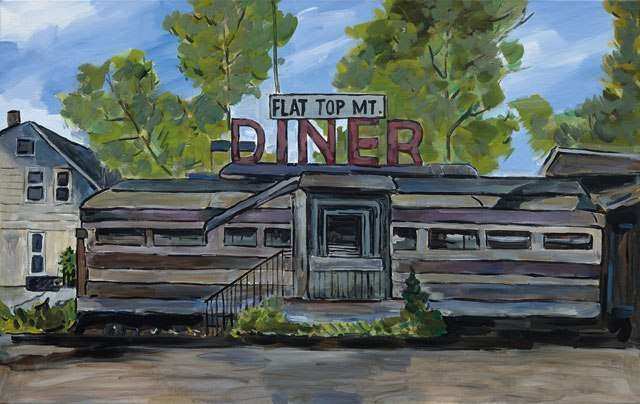

The London show, in production for the last two years with the theme of the American landscapes, offers recognizable canvases that are in closer in content to happier-faced Edward Hopper. The difference is that Hopper saddened us with dreary people slumped over in a downtown diner. Dylan’s landscapes are brighter, sometimes cornier and David Hockney-like. Compared to his songs, his canvases are not altogether, well, what we know to be Dylanesque.

Staying out of the mainstream and traveling the back roads, free-born style

Spread across three floor and number a few hundred works, Dylan’s canvases explore (as Hopper did) ordinary Americana in major cities in middle America on the back roads, motels, places off the beaten track that the title references. His landscapes picture places that any ordinary person might see when walking down the street or sitting at a bus stop or from a restaurant or diner in Kansas. The paintings at the London gallery reflect Dylan’s nearly constant travels throughout the United States on the never-ending music tour. His choice of subject matter reflects a deep affinity for the North American scene.

But where Edward Hopper was a gloomy nighthawk, Bob Dylan’s traditionalist art looks at the world from the cotton-candy vantage point of doves and birds on a park. He likes curious roadside attractions and respects for industrial might. Being from Hibbing, Minnesota, Dylan’s paintings feature fragments from his travels, pieces picked up as he passes across the land.

“For this series of paintings the idea was to create pictures that would not be misinterpreted or misunderstood by me or anybody else,” Dylan writes in an essay he wrote for the exhibition, his most extensive prose writing since Chronicles. “When the Halcyon Gallery brought the idea of me doing American landscapes for an exhibition, all they had to do was say it once. And after a bit of clarification, I took it to heart and ran with it. The common theme of these works having something to do with the American landscape— how you see it while crisscrossing the land and seeing it for what it’s worth. Staying out of the mainstream and traveling the back roads, free born style.”

Exclusively placed in non-exotic settings within a defined space

In positing a different view of the American character, Dylan likens his painterly style to Wassily Kandinsky and Georges Rouault. It’s a nice thought but rather too vain and self-satisfied. After all, the Russian Kandinsky is credited with painting one of the first purely abstract works in 20th century American art.

“My idea was to keep things simple, only deal with what is externally visible.” he writes. “These paintings are up to the moment realism—archaic, most static, but quivering in appearance. They contradict the modern world. However, that’s my doing.”

What’s beautiful about the show is its surprising verve. It is a parade of whiplash curves, flying buttresses, pointed steeples, arches and waves. They are not gaudy or garish or gaga. They’re often gregariously figurative. Railways, skyscrapers, and suspension bridges vie with deserted side streets and overgrown motels for his attention. This is an America of fairgrounds and circuses, forgotten crossroads and neglected cityscapes.

Unlike his Nobel Prize–decorated lyrics, Bob Dylan enamors us with a panoramic vision of America, as can be discerned in his kaleidoscopic 1975 song “Tangled Up in Blue.” In every picture the viewer doesn’t have to wonder whether it’s an actual object or a delusional one.

Dylan turns out to be a solitary road warrior with a sketchbook, looking at the country from odd angles. See these roads below? See the flowing or curved lines, suggesting far distances and the twilight of highway horizons? They mirror David Hockney’s child-like visual imagery, don’t they? Well, they’re as close to My Own Private Idaho as Dylan the painter gets.